The Reserve Bank raised the base interest rate by a modest 0.25% yesterday. But even modest moves carry outsized consequences for many. Harry Chemay reports.

“The Board judged that inflation is likely to remain above target for some time and it was appropriate to increase the cash target rate.”

So held the Monetary Policy Board of the RBA, apparently unanimously, as the central bank lifted interest rates 0.25% to 3.85% yesterday, after the brief 0.75% reprieve of 2025.

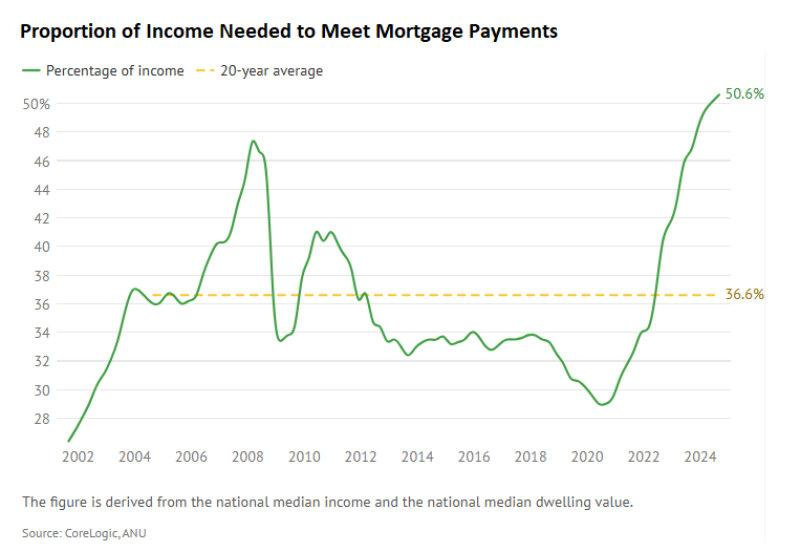

In an economy where the combined capital’s median dwelling price just crossed the $1m barrier and households collectively owe some $2+ trillion in mortgage debt, modest moves now carry outsized consequences for many.

Here are the winners and losers from yesterday’s decision (spoiler alert: it’s mostly losers).

Renters locked out, looking in

For hopeful homeowners who haven’t cracked the property market, this rate rise will be salt in an already festering wound.

Lender serviceability buffers mean each rate rise compresses maximum loan sizes,

narrowing the pool of accessible properties even further in a hot market.

With the national average first home buyer mortgage now north of $520,000, even a modest rate lift takes many a prospective first home buyer out of the race.

Older renters, those aged 40 to 55, face something closer to permanent exclusion. Melbourne Institute research shows low-wealth households had zero property net wealth at every survey point across the study. What awaits them? Retirement without housing wealth, almost certainly reliant on the Age Pension while potentially still paying rent (for which Commonwealth Rent Assistance provides scant relief).

Young and middle-aged mortgage holders

Here’s where rate rises tend to bite the hardest. Try servicing a 30-year $800,000 principal and interest mortgage at 6.25% p.a. on median NSW household income – that’s nearly $5,000 per month on a monthly take-home pay of around $9,500.

There would appear to be no relief in sight.

Middle-aged homeowners who’ve been in the housing market for years should theoretically have sizeable home equity, but many have re-leveraged, increasingly turning houses into virtual ATMs. Between 2000 and 2009, research has shown that one in five homeowners aged 45 to 64 increased their mortgage debt despite not moving house.

The RBA has previously acknowledged this property price ‘wealth effect’ as material to private consumer demand, yet noted yesterday that “growth in private demand has strengthened substantially more than expected, driven by both household spending and investment.”

Not a Goldilocks-level of household spending, but a little too hot for the RBA’s liking.

Wealthy on paper but cashflow constrained and vulnerable to rate movements; that’s middle Australia in 2026 – a group squarely in the crosshairs of modern monetary policy whenever aggregate household spending needs to be reined in.

Wealth inequality. Housing cost is hollowing out middle Australia

Older mortgagors

Approaching retirement with outstanding mortgage debt was once rare. No longer.

ABS data shows the average mortgage outstanding for those aged between 55 and 64 to now be more than $230,000, with real mortgage debt for over-55s increasing by more than 600 per cent between 1987 and 2015.

This new rate rise forces difficult choices on older employees: work beyond 65, or dip into super to escape the debt noose at retirement. Either way, the Big Four banks are in a no-lose position.

Retired mortgagors are even more vulnerable. Living on fixed incomes, primarily the Age Pension (of around $1,800 per fortnight for homeowning couples), they face an impossible arithmetic where mortgage repayments consume a substantial portion of their modest household budgets.

This (modest) rate rise may tip some from manageable stress into genuine financial hardship.

Mortgage mountain. Our $2.3 trillion debt and the ‘Big 4’ oligopoly.