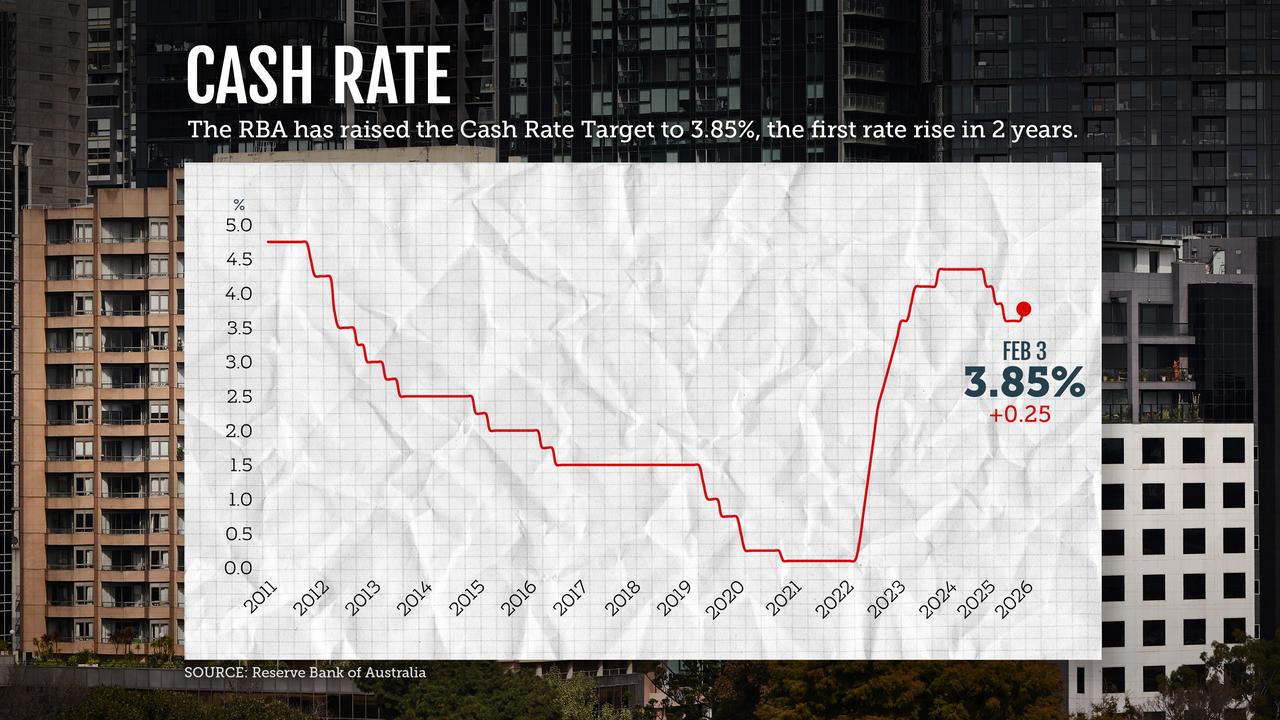

The Reserve Bank’s decision to lift the benchmark borrowing rate to 3.85 per cent has brought an end to the shortest easing cycle in the inflation-targeting era.

Given the central bank’s dramatic U-turn from cuts to hikes in the space of six months, the opposition was quick to point the finger at Treasurer Jim Chalmers after the RBA confirmed its move on Tuesday.

“This rate rise is not an accident,” said Opposition Leader Sussan Ley and shadow treasurer Ted O’Brien in a joint statement.

“It is the direct consequence of Labor’s addiction to spending, which has kept inflation higher for longer and left the RBA with no choice but to keep tightening.”

With the RBA board saying it had no choice but to hike rates after a modest increase in demand caused a “material” increase in inflation pressures, the opposition argued it was government spending that pushed the economy over its speed limit.

Dr Chalmers’ mid-year budget update, delivered in December, showed government expenditure is expected to rise to 26.9 per cent of GDP this financial year – the highest level in decades, excluding the pandemic.

The Reserve Bank’s updated forecasts, also released on Tuesday, showed public demand exceeded their previous estimates in November.

Their forecast for public demand was 0.1 percentage points higher in 2025 and 0.2 percentage points higher in the year to June 2026.

But this was nowhere near the upside surprise they copped from higher private demand, as governor Michele Bullock said in her post-meeting press conference.

“What’s happened over the last six months or so is that private demand has turned out to be much stronger than we had been forecasting,” she said.

Dr Chalmers was quick to point out that the RBA had singled out private demand as the culprit.

“What we’ve seen in our economy is public demand in retreat over the course of the last year, private demand growing strongly, and that explains the additional pressure on inflation,” he said during question time.

But Ms Bullock noted Australia’s productivity growth was so dire that the economy could not sustain a higher level of growth without price pressures kicking off.

Deloitte Access Economics partner Stephen Smith said the blame extended beyond the current government.

“The fact that an economy growing at 2.3 per cent breaks out in inflation sweats points to a more fundamental problem in our economy – our poor capacity to produce goods and services and our low run rate,” Mr Smith said.

“That we are here is an indictment on the piecemeal and lacklustre nature of reform over the last three decades.”

The result is lower forecast growth in household disposable income – essentially, living standards.

“This is not ambition for Australia,” Mr Smith said.

“If this is really as good as it gets for economic growth, then Australia has bigger problems than an interest rate rise.

“Today’s decision will increase the pressure on the May budget to deliver meaningful reform that boosts investment, drives productivity, and delivers an economy that can grow faster without inflationary pressures.”