While the NSW police have yet to make any statements about the surviving Bondi killer, Naveed Akram, his links to ISIS abound. Human rights analyst Al the Writer reports (Part 2).

In part 1, we covered how the police and ASIO may have ignored the many links between the Bondi perpetrators and ISIS. Here, we look closer at the links between Akram, known ISIS operatives, and other atrocities committed in Australia, including the Wakeley Church attack in 2024.

In videos from 2019, a seventeen-year-old Naveed Akram stood outside Bankstown train station, preaching about Islam. The Street Dawah Movement confirmed Akram appeared in its videos ‘a few times’ in 2019. The group released a statement saying Naveed Akram was not a member and that none of its members knew him personally. They also highlight that they provide a mental health referral service.

Dawah (or Da’wah) is an Arabic term meaning “invitation” or “call,” referring in Islam to inviting people to understand, embrace, or reflect upon the message of Islam.

Street Dawah

It is difficult to determine who runs the Street Darwah Movement, but many of those affiliated with Al-Madina Dawah Centre (AMDC) have also been associated with Naveed Akram’s dawah activities, including El Matari and others.

Wissam Haddad, also known as Abu Ousayd, operated a van street-preaching service, officially registered as its own entity in 2022. Haddad’s Dawah Van Incorporated was registered as a charity to preach on Sydney’s streets, but was stripped of its charity status after a Four Corners episode.

It is unclear whether Naveed Akram’s Darwah activities were linked to Haddad, given the amorphous nature of associated structures. Curiously, though, Haddad highlights that the undercover agent Marcus interviewed by Four Corners allegedly appeared in the background of a Darwah YouTube video that Naveed Akram was seen preaching in.

The video was posted in 2022, but has since been removed. However, if true, it implies that ASIO operatives were possibly spying on Naveed Akram well before 2019, yet his father was still maintaining a gun license during this time.

It is important to note that this story, while establishing links between the Bondi attackers and ISIS-linked extremists in Australia makes no imputations as to any involvement by groups or persons named here in the actual attacks – apart from Naveed Akram himself. Naveed is in custody.

Youssef Uweinat

A known associate of Naveed Akram is Youssef Uweinat. Uweinet was associated with both the Street dawah movement, El Matari and Haddad.He acted as a youth leader at Haddad’s prayer centre and served almost four years in prison for grooming minors to launch attacks via Haddad’s AMDC in Bankstown.

After his release, he was photographed in August 2025 waving a black flag, often associated with ISIS, on the Sydney Harbour Bridge during a pro-Palestine protest, where he was documented ambushing and harassing other Muslim protesters.

Both Haddad and Uweinat, who have no interest in a Palestinian state, were said to be exploiting the Palestine movement as part of a broader ISIS recruitment strategy, despite the significant opposing interests of the groups.

Youssef Uweinat and Wassim Haddad

Isaac El Matari

Among the other individuals connected with Naveed Akram was Isaac El Matari, who declared himself the ‘Australian commander’ of Islamic State. El Matari was sentenced in 2021 to seven years and four months for plotting terrorist attacks, with eligibility for parole in January 2025.

The NSW Supreme Court heard that El Matari had developed grandiose plans to establish an insurgency in rural Australia. He mentioned specific targets, including Sydney’s St Mary’s Cathedral, the American embassy, and spoke of ‘conquering a small town or village,’ specifically naming Orange. He declared, ‘I know what targets will make people scared and will convey our message.’

El Matari’s radicalisation followed a familiar pattern. Prosecutor Sophie Callan told the court that El Matari left Australia when he was eighteen but was arrested in 2017 and incarcerated in Lebanon for seeking to join Islamic State in Syria. After spending nine months in the notorious Roumieh prison in Lebanon, where his defence claimed he was tortured, he returned to Australia in June 2018.

Rather than being deterred, the court heard that the depth and extent of his radicalisation continued up until his arrest in July 2019—the same period when Naveed Akram was appearing in Street Dawah Movement videos.

What makes El Matari particularly significant is his documented connection to both the Street Darwah network and direct association with Naveed Akram during his radicalisation. Prime Minister Albanese confirmed that two of the people Akram was associated with in 2019 were charged and went to jail, but Akram was not seen at that time to be a person of interest,

with ASIO concluding there was no indication of any ongoing threat.

Radwan Dakkak, also believed to be an associate of Akram’s received eighteen months for ISIS membership and distributing propaganda through media outlet Al-Tayr. He was arrested alongside El Matari in the same July 2019 operation that should have flagged Naveed Akram as a serious threat.

The Wakeley Church attack

It is not only the Akrams that are said to have an affiliation with AMDC but also the Wakeley Church attacker, who stabbed Bishop Emmanuel. This was stated by the agent talking to the ABC, who recognised the Wakeley attacker from the Al Madina Darwah Centre.

On April 15, 2024, a sixteen-year-old boy stabbed Bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel during a live-streamed sermon at Christ the Good Shepherd Church in Wakeley. During the attack, the teenager shouted ‘Allahu Akbar’ and was heard saying if the bishop had not insulted his prophet, he would not have come. Police classified the attack as terrorism, finding it was religiously motivated.

Officers seized the attacker’s phone and discovered he was part of a WhatsApp group called ‘Brotherhood’ with other teenagers who expressed sympathies with violent extremism and highlighted Bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel as a target. According to the ABC interview, AMDC operatives were also part of this group.

The attack triggered Operation Mingary, which saw more than four hundred officers execute thirteen search warrants across Sydney suburbs, including Bankstown, the location of AMDC. Seven teenage boys were arrested, ranging from fourteen to seventeen, with five charged with conspiracy to plan terrorist attacks.

Due to their status as minors, we are unable to further examine allegations of their affiliation with the AMDC; however, the geographic focus on Bankstown and the arrests of seven teenagers with ISIS sympathies suggest authorities were likely examining whether the same radicalisation networks that produced Naveed Akram were also influencing this new generation of teenage extremists.

Al-Risalah Islamic Bookstore & Centre

The AMDC was not Haddad’s first foray. In 2012, Haddad opened the Al-Risalah (‘The Message’) Islamic Centre and bookstore in Bankstown in western Sydney, which quickly ‘gained a reputation as a centre of Islamic extremism,’ according to an ABC 7.30 investigation.

By 2013, it had become a hub for extremist preachers recruiting young Australian Muslims to illegally travel to Syria to fight for, or to join humanitarian missions associated with, Islamist groups there.

Among the preachers who lectured at Al-Risalah were Abu Sulayman (Mostafa Mahamed Farag), one of Australia’s highest-ranking Al-Qaeda terrorists in Syria, who became spokesman for Jabhat Al-Nusra, and Khaled Sharrouf, an infamous ISIS terrorist who posted photos of his children holding severed heads.

Khaled Sharrouf frequently visited Al-Risalah before travelling to Syria. Other lecturers at the centre were Mohamed Elomar, Sharrouf’s best friend and fellow ISIS fighter (who married Sharrouf’s 13-year-old daughter and also posted severed head photos), Bilal Khazal, sentenced to 14 years for producing a terrorist handbook on downing planes, and Junaid Thorne, a pro-ISIS preacher who co-founded the Brothers Behind Bars organisation with Haddad.

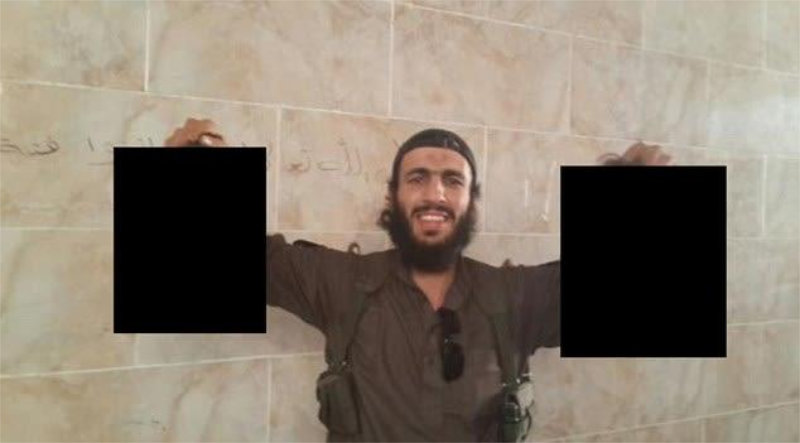

Mohamed Elomar

Al-Risalah was raided in September 2013 and closed in October 2013.

In January 2015, police raided Haddad’s home in Leppington in western Sydney, uncovering weapons, a machete hidden under his bed, ISIS DVDs (including sermons by former al-Qaeda in Iraq leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi), and an ISIS flag, along with dozens of newspaper clippings about counter-terrorism operations and arrests in Australia.

He escaped a prison sentence despite having been caught in illegal possession of three weapons (two tasers and a can of capsicum spray) hidden in his house.

Wassim Fayad

Another key figure connected to Wassim Haddad’s network was Wassim Fayad, also known as Fadi Alameddine or Abu Zakariyah. In December 2023, Fayad was filmed with Haddad’s Dawah Van.

Fayad’s criminal history reveals a pattern of violence justified through religion. In 2013, Al Jazeera reported that Fayad was sentenced to at least sixteen months in jail for whipping a Muslim convert forty times with an electric cord as religious punishment. Sydney Central Local Court Magistrate Brian Maloney told Fayad during sentencing: ‘You have brought much shame upon the Islamic faith.

Most significantly, ABC Investigations revealed that in 2015, police alleged Fayad was part of an Islamic State cell whose young members visited him in prison while he served his sentence for the whipping attack. Several of these young men went on to commit terrorist acts, including assisting the fifteen-year-old boy who murdered police accountant Curtis Cheng in October 2015.

Rising Extremism

While unrelenting calls for a Royal Commission on antisemitism persist, it is important that any investigation examine the full spectrum of violent extremism, its roots and avoid the politicisation we have seen in areas such as the Antisemitism Envoy’s role.

In part 3, we will delve into the methods and targets of radicalisation.

Warnings of ISIS links ignored. The anatomy of the Bondi attacks