In Australia, a child of ten can go to prison for shoplifting, while an executive engaged in multimillion-dollar bribery gets away with a fine. Aleta Moriarty with the story.

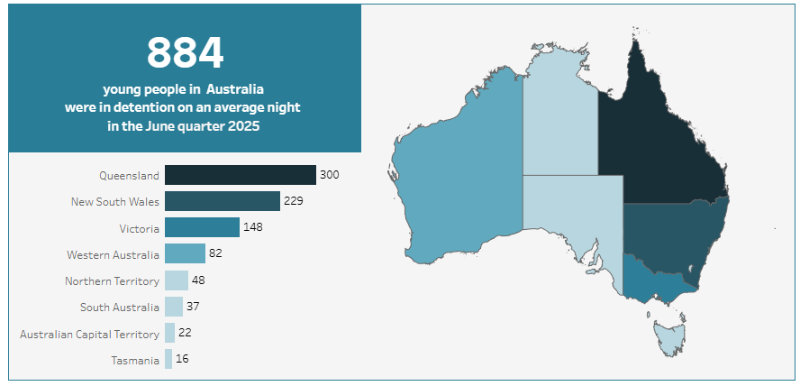

On an average night in 2025, there were approximately 884 young people in detention and over the course of a single year, 4,578 children passed through detention.

Meanwhile, David Savage, former COO of Leighton Holdings, was fined ($) just $1000 for his role in orchestrating what the Australian Federal Police describe as Australia’s longest-running corporate bribery investigation, concealing approximately $45m in bribes to Iraqi politicians. However, after pleading guilty to Corporations Act breaches, he got a small fine and was able to retreat back to his estate in France.

As Clancy Moore of Transparency International Australia has noted regarding cases like this: “In almost 25 years, only seven individuals and three corporations in Australia have been convicted of foreign bribery.”

The Iraqi middleman who distributed portions of the bribes received over three years in a UK prison. But he lacked the advantages of Australian corporate citizenship.

UN Condemnation

Recently, during the UN Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review, Australia was urged by more than 40 countries to raise the minimum age of criminal responsibility from 10 to 14. Nationally, young people may be charged with a criminal offence if they are aged 10 or older in all jurisdictions except the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory.

Hugh de Kretser, President of the Australian Human Rights Commission, stated:

“Locking primary school age children in prison harms them, disrupts their education and increases the risk of further involvement in crime. It goes against medical advice and is out of step with global human rights standards. If we want to close the widening gap on Aboriginal overimprisonment, this must change.

“The Australian government could show national leadership by increasing the minimum age of criminal responsibility in Commonwealth law to 14 years and encourage the states and territories to follow.”

Rather than heeding any such advice, Australian states are accelerating in the opposite direction. Victoria’s “Adult Time for Violent Crime” policy, announced in November 2025, will treat 14-year-olds as fully formed moral agents deserving of adult prison, potentially life imprisonment ($).

Children incarcerated

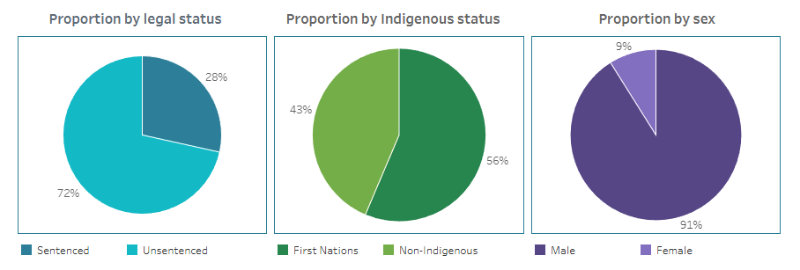

The majority of young people in detention are unsentenced on remand, awaiting a court date, with the average time detained unsentenced being 6 days.

Source: aihw.gov.au

A Productivity Commission report states imprisoning children costs taxpayers in excess of $1B annually, with each detained child costing taxpayers $3,320 per day or $1.212m per child per year.

One could only imagine the different outcomes that could be achieved if that funding were diverted to early interventions, social, therapeutic or education resources instead. For example, research shows that more than 17% of incarcerated Indigenous Australians report having been removed from their natural family compared with 7% of those who had never been incarcerated.

But that’s not the case. What we know is juvenile detention is a revolving door, where

children who go in almost never come out.

According to data from the Justice Reform Initiative, 84.5% of children released from detention return to sentenced supervision within 12 months.

Victoria’s Sentencing Council research found that once children enter the youth justice system, they are much more likely to reoffend, and that those children first sentenced between ages 10 and 12 had a six-year reoffending rate of 86%, more than double the rate for those first sentenced at 19–20.

A 2025 UNSW study examining over 1,500 justice-involved young people in NSW found that those incarcerated during adolescence faced a fivefold increase in the risk of being incarcerated as an adult, compared to young people who had never been in custody.

First Nation children overrepresented

The impact of this crisis in mass incarceration of young people falls overwhelmingly on our First Nations children. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s 2024 Youth Detention report, First Nations young people made up 60% of all youth detainees in the June quarter 2024,

despite comprising just 6.6% of the Australian population aged 10–17.

They are 27 times as likely as non-Indigenous young people to be detained. In the Northern Territory, the situation reaches its most extreme: 95% of detained children are Indigenous. Children aged 10–13 face the starkest disparity: First Nations children in this age group are imprisoned at 45.5 times the rate of their non-Indigenous peers.

Source: aihw.gov.au

This rate of incarceration has lifelong impacts. Consider this: according to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework, around 10% of Indigenous Australians aged 20–64 hold a Bachelor’s degree or above, compared to 35% of non-Indigenous adults. Now set that against this: according to BMC Public Health, approximately 15% of Indigenous Australian men report having been incarcerated at some point in their lives, with roughly 3% are in prison at any given, This shows the damning evidence that

an Indigenous man in Australia is much more likely to be imprisoned than to be university educated.

While all criminals are equal, some criminals are more equal. Nowhere have we seen the scales of justice so rapidly distorted as in the Epstein files release, where we have seen scores of world leaders and business elites embroiled in child trafficking and paedophile scandals, many remaining un-investigated, uncharged and untouched.