The conservative commentariat that didn’t want rate cuts last year is urging the RBA to increase rates tomorrow, but it may not happen, Michael Pascoe writes.

The money market betting is that the Governor Michele Bullock will announce a 25-point rate rise Tuesday afternoon. The herd is following the preferred commentary of the national media, much of which hasn’t forgiven the RBA for cutting rates last year.

It’s against the market odds, but not impossible for the RBA to look beyond the headline figures and see that the case for an immediate rise isn’t clear, that there was both noise and irrelevant numbers in the December quarter consumer price index. Quick and easy example: overseas travel and accommodation accounted for nearly all the December inflation, as the Australia Institute’s Matt Grudnoff has explained.

It would be worse than silly to increase Australian unemployment because of the price of hotels in London and Paris, or think that such costs are domestically contagious.

The rise in the annual trimmed mean figure was only 0.05%, just enough to move the rounded-up headline. The seasonally adjusted CPI for the month of September was 0.2%. Annualise that, and it would be monetary Christmas all year round.

Politicised economists

The conservative columnists sometimes use a neat little slur against those not as monetarily hawkish as themselves, “Labor-aligned economists”. No doubt they would bridle at being called “LNP-aligned”.

It might be fairer to call them “capital-aligned” as their regular chorus tends to be about labour with a “u” not being cheap enough and productivity not being high enough because labour isn’t flexible enough, with “flexible” in this instance often being a euphemism for “cheaper”. It’s up there with the dogma that Labor’s fiscal policy caused all the inflation.

(No, Anika Wells’ expensive trip to New York was in the September quarter.)

What the commentariat absolutely does not like is a “tight” labour market. What it never seems to grapple with is the idea that we need a

“tight” labour market to encourage capital investment to, yes, improve productivity.

The RBA regularly wrings its metaphorical hands and ties itself in rhetorical knots over the labour market being “a bit tight” without defining if that’s “too tight” and forever hoping that somewhere out there will be the Goldilocks “just right”.

Unemployment conundrum

The major problem for the hawks is the idea that unemployment can be low and the labour market “a bit tight” without causing rampant inflation, despite the evidence of recent years that it is indeed possible.

You don’t have to be “Labor-aligned” to think the RBA would be wise to wait another month or three. The very unaligned economist Gerard Minack, in his latest report for clients, said he wasn’t as sure as the market that the RBA would tighten this week, citing the “noise in the data” with government subsidies affecting housing and utility prices and the ABS still bedding down its new monthly CPI series.

Minack states that underlying inflation is sticky “in part because weak productivity implies that current wage growth is too high and in part because high migration is pressuring housing costs”, but he goes beyond the pet shop galahs in looking at the RBA’s key assumptions, starting with that relationship between unemployment and wage growth.

“From 2013, wage growth was persistently lower for any given unemployment rate than it had been in the prior 15 years,” he wrote. “If that post-2013 relationship persists, then an unemployment rate around 4% would lead to wage growth of around 3½% – a pace the RBA had seen as consistent with its 2-3% inflation target.

“The second assumption is what level of wage growth is compatible with the Bank’s inflation target. Historically, the Bank seemed to believe that the sweet spot for wages was 3-3½% or 3¾%. Private sector wage growth is in that range (as measured by the Wage Price Index), yet inflation is not in the Bank’s target range.”

Productivity galahs

Yes, it is a productivity thing, “trend (three-year average) unit labour costs rising too fast to be consistent with a return to target inflation”.

The “renowned macroeconomist”, as the AFR called Minack, made headlines in 2023 for saying ($) “Australian policymakers are ‘doubling down on a dumb strategy’ by relying on population growth rather than increased investment to grow the economy.”

He remains on the population versus investment issue:

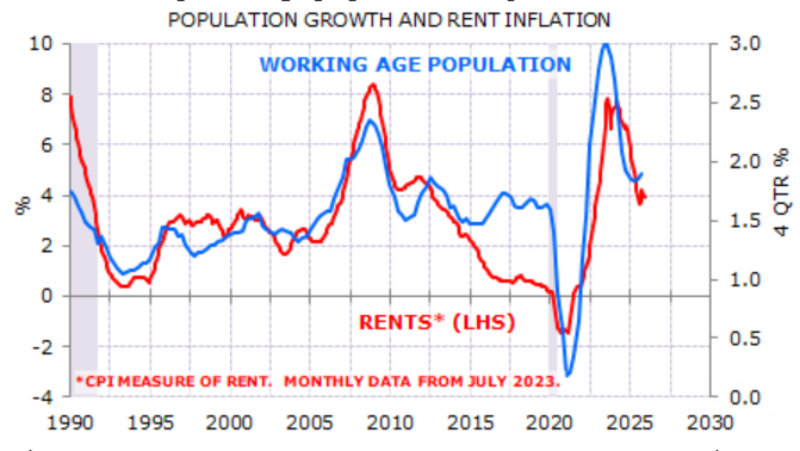

“Is Government policy contributing to inflation? Every galah in the national financial press menagerie is squawking about how high government spending adds to inflation. They’ve got it wrong. The government policy that is contributing to high inflation is fast migration-led population growth. Housing construction and rents are the two largest items in the CPI. Both contributed to the second-half rise in inflation. Both are driven in part by population growth.”

“Like the RBA, I was wrong-footed by the pick-up in inflation through 2025. I should have put more weight on the implications of poor productivity and fast population growth for inflation. In hindsight, the RBA did prematurely ease policy last year.

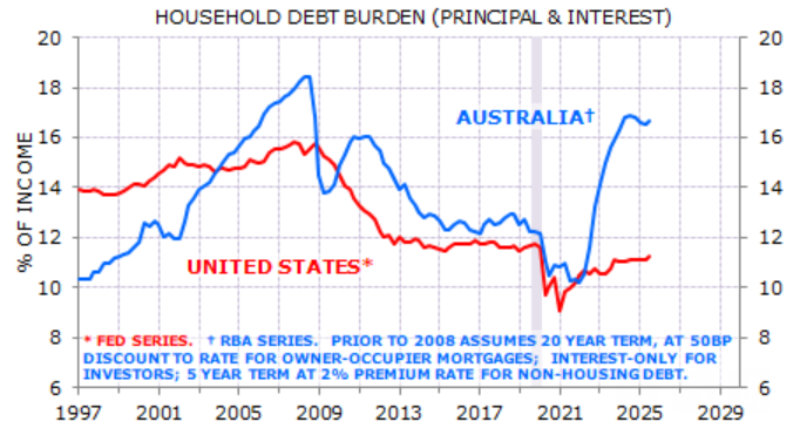

“However, I still think policy is restrictive. RBA tightening has, for example, had a much larger impact on household finances than Fed tightening. If the Bank does reverse course and tighten – if not this week, then in May – then it seems likely that Australian growth will start to decelerate through the second half.”

That final insight is what Minack Advisors’ clients pay money for. While media concentrate on how many dollars a month mortgages might change, the bigger call is that a Reserve Bank cut will see the Australian economy start slowing with all that implies for investors.

And it’s not as if the economy is growing strongly now, remaining dependent on fiscal stimulus and that double-edged population growth to maintain consumption.

Given the downside risks,

the RBA’s still-new monetary policy board would do well to be certain it’s not jumping at noise,

either from the ABS or the pet shop.

Yes, some CPI figures rose, but they could easily fall again in the current quarter. The assumption of a rate rise already has the RBA being whipped for backflipping. It would be a more painful flop if the figures flipped again.