An investigation into Inpex, and its gigantic Ichthys gas project, reveals the systemic failure of Australia’s tax system and some corporate shenanigans. Josh Barnett and Michael West report.

When INPEX sought approval to develop the Ichthys gas field in 2008, Australians were promised decades of shared prosperity. A 40 year project life. Billions in economic benefits. A nation that would be richer for allowing one of the world’s largest LNG developments to extract and export its gas.

More than a decade on from first production, the numbers tell a very different story.

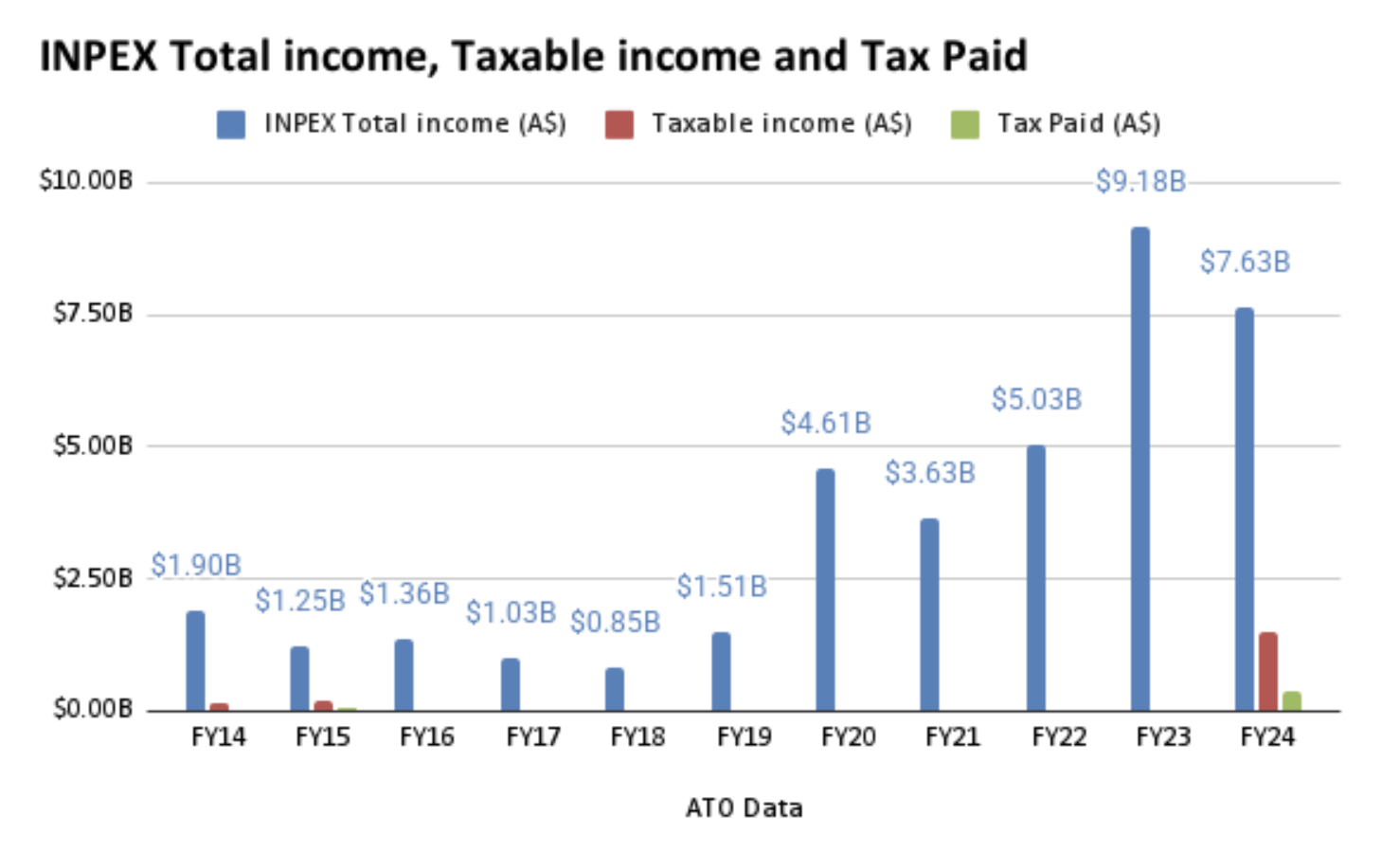

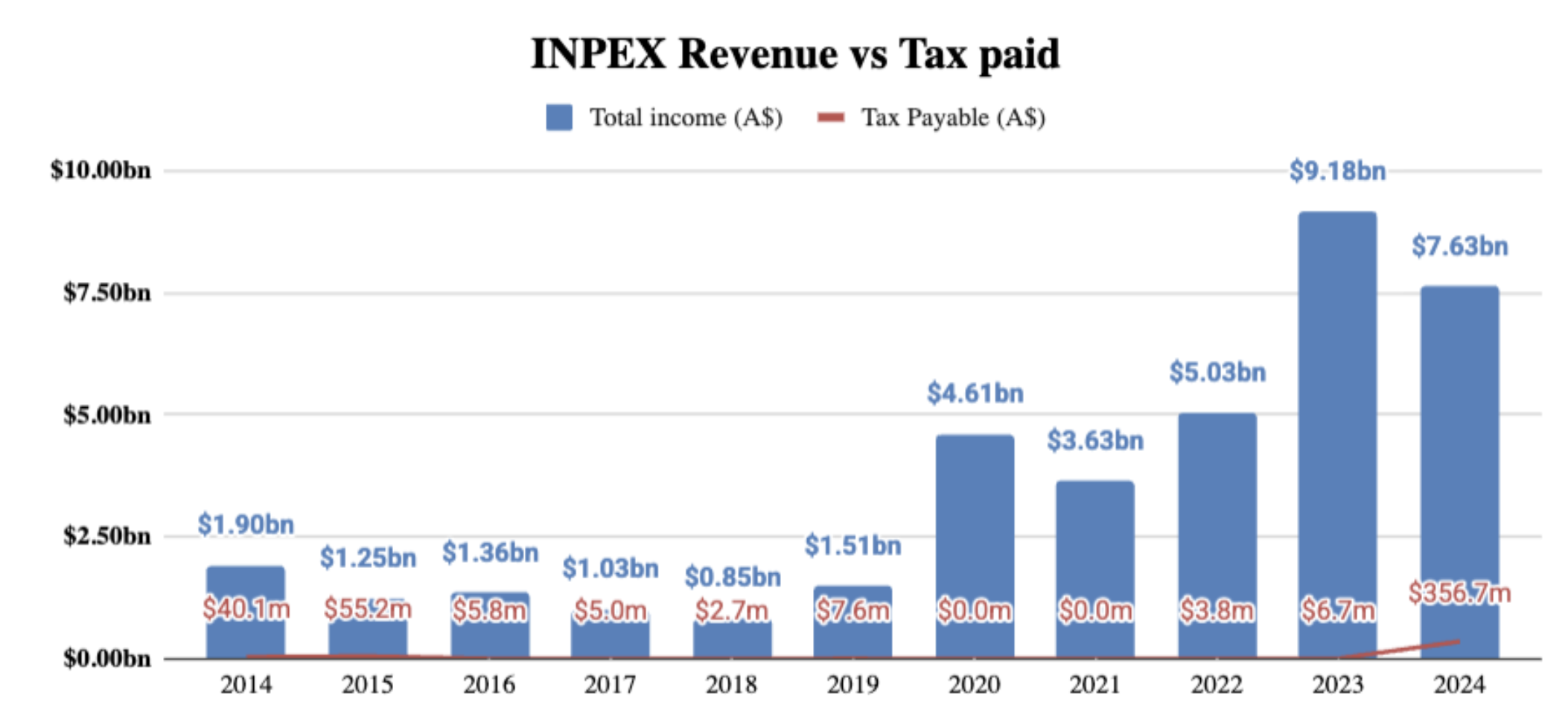

According to Australian Taxation Office transparency data, INPEX’s Australian entities have booked more than $36 billion in revenue over the past 11 financial years. Over that same period, they have paid less than $500 million in corporate income tax. In many years, they paid nothing at all.

In FY23, as energy prices surged globally, INPEX entities recorded more than $9 billion in revenue in Australia. Their taxable income that year was just $23.5 million. The tax paid amounted to $6.7 million, around 0.07 per cent of revenue.

The Inpex justification

Responding to questions by MWM, Inpex defended its tax structures, pointing out that tax is paid on taxable income (or profits) rather than revenue (or total income).

This is correct, although the Tax Office itself uses total income as a key metric on tax avoidance because multinationals shed an enormous amount of their tax liabilities between the total income and taxable income lines.

The corporate tax rate is 30%; but 30% of zero is zero.

Much of this money from ‘total income’ is siphoned offshore by interest on loans from related companies before it gets to become ‘taxable income’. Inpex is by no means alone. Stemming tax ‘leakage’ is standard industry practice.

Chevron, Exxon, Shell and others aggressively engage in this practise of ‘debt loading’, transfer pricing, and other aggressive tax reduction schemes too.

The aim, overall, is not to make a profit here as tax is levied on profit.

It is also fair to point out, as Inpex notes, that the massive capital investment involved with these gas projects delays tax for years, quite legally. All of which brings us to the nub of the matter, systemic failure to capture enormous wealth from the resources which all Australians own.

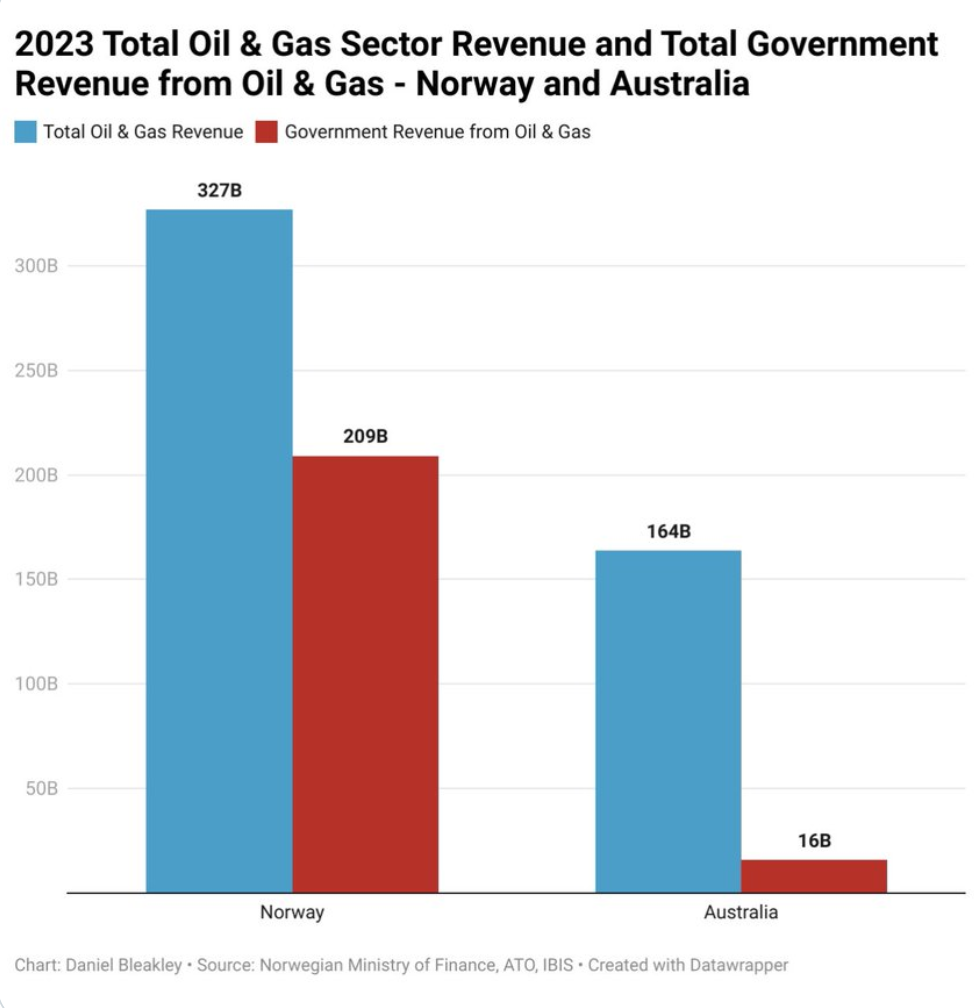

A failure which is put into stark relief by the likes of Norway and its sovereign wealth fund which capture this wealth for their citizens rather than see it funnelled off to foreign shareholders.

The Norwegian sovereign wealth fund delivered $350B to its citizens in 2025. Norway taxes gas at 78%.

Baby steps, baby tax

So it is that ten years down the track and Inpex is beginning to pay what looks like large amounts of tax, but in the scale of things – versus its income – it’s not much.

In FY24, INPEX’s tax payments rose sharply, with $356.7 million paid on $7.63 billion in total income. But that spike only arrived after years in which the group’s Australian entities had recorded billions in revenue while paying little to no corporate tax.

The flagship Ichthys LNG project itself has never paid corporate income tax in Australia, despite generating tens of billions of dollars in income since production began. This goes to another problem with the tax system and its approach to foreign entities exploiting Australia’s resources.

Profits on one project can be written off – so no tax is paid – against tax losses on another project. So it is that foreign gas multinationals have for years paid no tax while racking up gigantic revenues.

“Optimising tax” is part of the business model

INPEX doesn’t hide its approach to tax. It advertises it to its shareholders

In its February 2025 results presentation, the company’s executives told shareholders they would “continue to optimise” income tax, and then spelt out the commercial logic in plain language:

“To put it bluntly, if we can reduce our income tax expense by 1% out of the ¥900 billion, profit will increase by around ¥10 billion.”

Reducing tax is treated as a straightforward profit lever.

Years of enormous revenue flowing through INPEX’s local entities, accompanied by minimal taxable income and little to no corporate tax paid.

The shenanigans

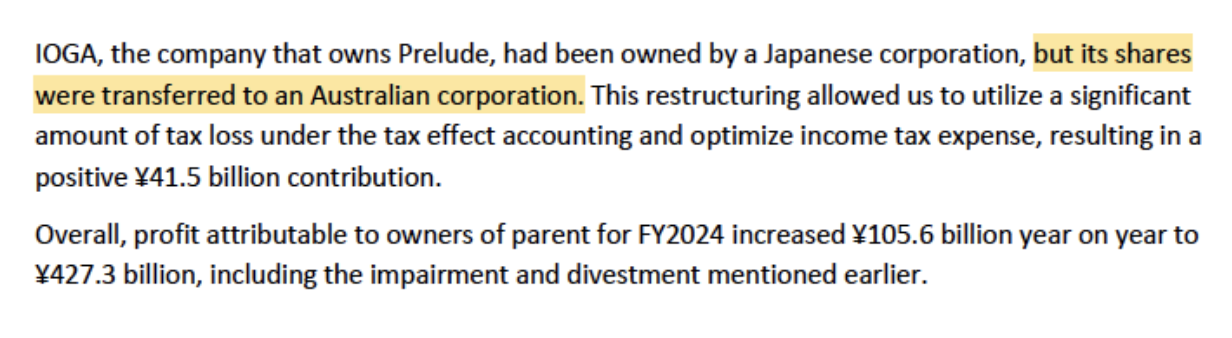

A shareholder presentation shows how central tax outcomes are to the business model. In its FY2024 results briefing, the company described a group reorganisation involving IOGA, the entity associated with the Prelude asset, where

shares were transferred from a Japanese corporation to an Australian corporation.

INPEX said the restructure “allowed us to utilise a significant amount of tax loss under the tax effect accounting and optimise income tax expense”, producing a “positive ¥41.5 billion contribution” to profit.

On the face of it, this would appear to be a direct admission by Inpex that they cooked up this restructure for the purpose of dodging their tax obligations.

This sort of practice, paper shuffling, is highly questionable. If it is done primarily to avoid tax then it is illegal under Australia’s tax laws, but it is notoriously difficult for authorities to prove ‘intent’ to defraud. What was in the mind of the Inpex directors and executives, their auditors EY and their tax lawyers when they concocted their ‘group reorganisation’?

Subsidise the losses, privatise the profits

INPEX’s Australian gas empire hasn’t been built on private capital alone, it has been enabled by taxpayer funded infrastructure designed to service the fossil fuel supply chain.

The clearest example is Middle Arm in Darwin, a major industrial expansion pitched as “sustainable development” but widely criticised as a gas and petrochemicals hub by another name.

Greenwashed: how the new “Middle Arm” fossil fuel hub was rebranded green

The Albanese Government committed at least $1.5 billion in Commonwealth equity for Middle Arm’s “common user” enabling infrastructure, while a Senate inquiry has referenced the Commonwealth injection as $1.9 billion.

On top of that, the NT Government committed $27 million for the precinct. Public money, in other words, is underwriting the platform. Yet in parallel, Australia’s fossil fuel tax settings continue to allow multinationals to defer liabilities and minimise payments for years, meaning the public finances the build while profits are exported and the tax take remains thin.

In other words, governments absorbed the risk, while companies absorbed the returns. And once the infrastructure is built, the Australian public doesn’t share in the upside. Inpex’s Australian entities have generated tens of billions in revenue, exported millions of tonnes of gas, all while returning little in company tax and zero royalties or PRRT.

As Mark Ogge of The Australia Institute frames it, Inpex exports more gas each year than in used by all consumers in NSW, Victoria and South Australia combined, while paying no royalties and no PRRT.

PRRT, the tax that never seems to arrive

The Petroleum Resource Rent Tax, PRRT, is supposed to clip the ticket on super profits from offshore oil and gas once projects have recovered their costs. In reality, companies can pile up deductible spending, exploration, development and financing costs, then carry them forward, with uplift, year after year, so “rent” stays negative on paper even while LNG exports roar on.

INPEX has paid $0 in PRRT, and a report from The Australia Institute notes that no gas company has ever paid PRRT on exported gas. INPEX itself does not expect to pay PRRT until at least 2030. Meanwhile, it exports about 9 million tonnes of LNG a year, more gas than is used by households and businesses in NSW, Victoria and South Australia combined.

Questions to Inpex

In response to our questions on tax, INPEX argues it is misleading to compare revenue to tax paid because corporate income tax is paid on profit after depreciation, not revenue.

It says it paid $2.069 billion in tax from 2011 to 2023, with a further $606 million in 2024, after the upstream Ichthys entity moved to “tax payable” in the 31 December 2023 income year once allowable losses were recouped. INPEX points to $76 billion in capital investment since 2011, operating costs of about $1.5 billion a year, and a workforce of over 1,400.

It confirms it has paid $0 in PRRT to date, but says it will begin paying PRRT from 1 July 2026 after amendments to the PRRT Assessment Act.

But the story is the gap between revenue and profit, and who designs it. Depreciation, deductions, carried forward losses and uplift can keep taxable income low for years while exports flow. The result is predictable, less company tax and delayed PRRT, with the public left covering the shared bill for infrastructure, regulation, and the broader risk baked into Australia’s gas settings.