Supporters of the Australian Defence Force being more closely integrated with the US military, and of AUKUS, seem convinced that we need the US to defend ourselves. Former senator and submariner, Rex Patrick, explains why they’re wrong.

While there are clear concerns in the US and Australia with China’s growing military power and how that power might be utilised, no-one reasonably thinks China has aspirations of attacking Australia. But, for defence purposes, we plan for worse-case, and so in assessing whether Australia could defend itself, a Chinese attack is a convenient scenario to explore.

Nuclear attack

It’s estimated China possesses more than 500 operational nuclear warheads, and by 2030, they’ll have over 1,000. Most of those will be aimed at US targets – US air and military bases in Guam and Hawaii, US bases in the territories of America’s allies in north-east Asia – Japan and South Korea; as well as a growing list of strategic facilities and cities in the continental United States itself.

And as China enters an era of nuclear weapon abundance, there’ll be long-range missiles and warheads to spare for US-related targets down under – the signals intelligence facility at Pine Gap near Alice Springs, the submarine communications station near Exmouth, the RAAF base at Darwin and naval facilities at Garden Island south of Perth.

It’s clear that an expanding US military presence in Australia has increased the likelihood of nuclear weapons being directed at us by China.

Our best protection against the risk of nuclear war is a government policy of support for the system of mutual deterrence and effective arms control. In this, the AUKUS program isn’t helpful as Australia’s past diplomatic engagement on nuclear arms control and non-proliferation has been downgraded as we try to persuade other nations that Australia should be permitted to receive weapon-grade plutonium from the reactors of our anticipated US and UK sourced submarine reactors.

Albo and the nukes – the demise of Labor’s disarmament policy

Conventional conflict and the tyranny of distance

Launching a conventional attack on Australia is a very hard thing to do.

Geography is our great advantage. What historian Geoffrey Blainey called the “tyranny of distance” is a big problem for any country wanting to attack Australia. In World War II, the invasion of Australia was operationally and logistically a bridge too far for the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy. During the Cold War, Australia enjoyed defence on the cheap because there was no direct conventional military threat from the Soviet Union.

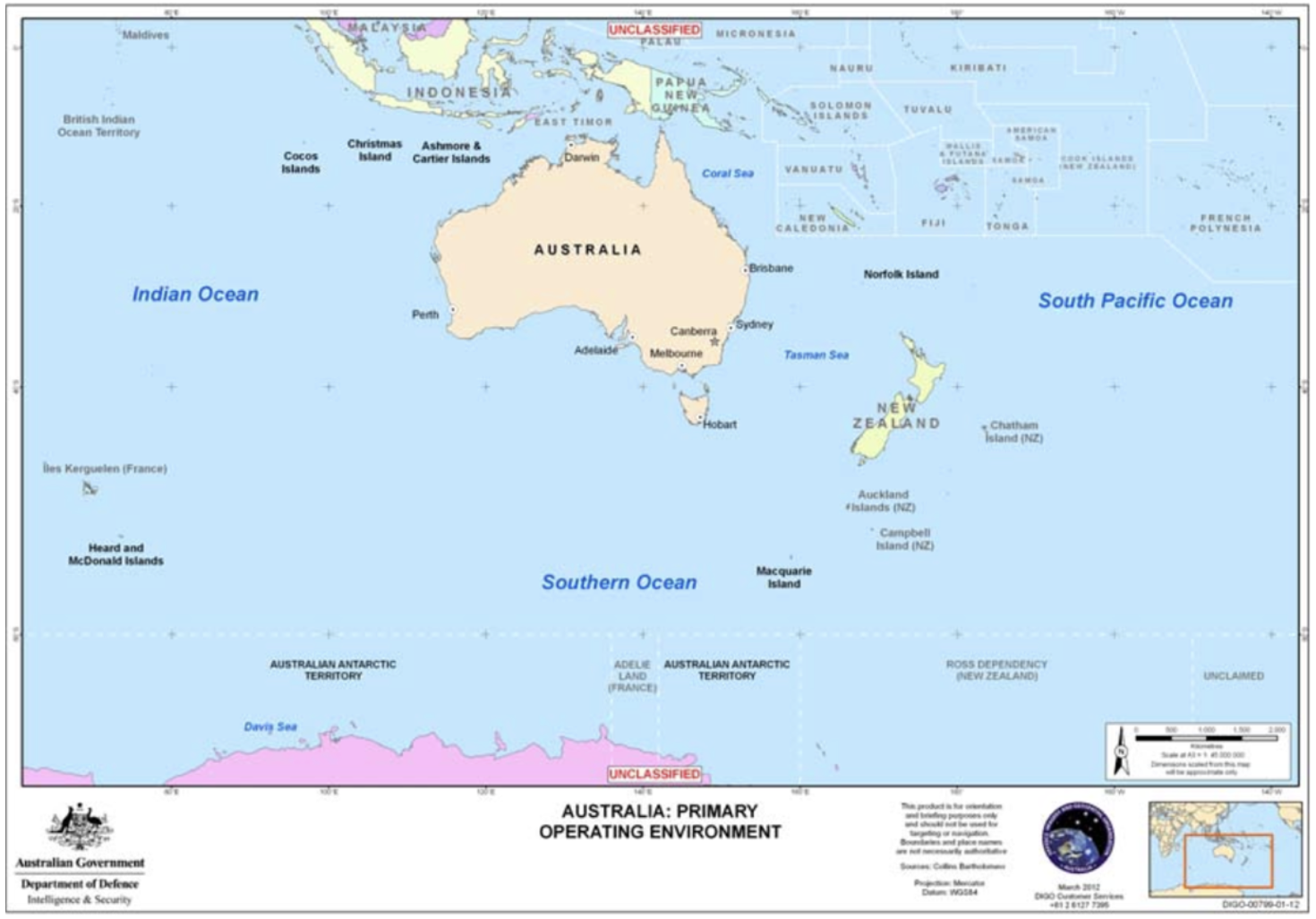

We’re a long way from China, surrounded by a ‘moat’ and are further assisted in our defence by an inhospitable vastness between a hostile force landing on our northern shores and our major population centres.

We can also afford to defend ourselves if we sensibly reallocate the $365B cost of eight AUKUS submarines to focus on the defence of Australia first.

Here’s how.

Keeping a watch

An intelligence capacity, focused on areas of primary strategic interest to support an independent defence of Australia, is crucial. This would involve cooperation with other nations (including as part of 5Eyes), defence-focused spying by the Australian Secret Intelligence Service and eavesdropping by the Australian Signals Directorate, covert submarine intelligence missions and intelligence collection by deployed RAN surface ships and RAAF surveillance aircraft.

Open source intelligence should not be discounted.

We also need a highly capable surveillance capability for detecting, identifying and tracking potentially hostile forces moving into our military area of interest.

Australia should invest in satellite surveillance system ($5B, leaving $363B in available funds from cancelling the $368B AUKUS program) to complement our three Over-The-Horizon Radars at Longreach in Queensland, Laverton in WA and at Alice Springs in the NT and double the size of our P-8 Maritime Patrol and Response fleet from 8 to 20 aircraft ($6B, $357B).

We should also invest in deployment of long-range acoustic systems ($1B, $356B), e.g. in places like Christmas Island to detect and identify foreign submarines transiting the Lombok Strait.

We need to ensure we have reliable ships and submarines with well-trained crews deployed in our northern approaches, particularly near the many southern exit points of the Indonesian archipelago.

Defending the moat

Defence of Australia, in the lead-up to conflict, would require sea and air denial.

To do this, we need all relevant defence assets to be capable of launching stand-off anti-shipping missiles, in particular the Naval Strike Missile and Joint Strike Missile, which will be made in a Kongsberg facility being built in Newcastle.

These missiles would be an essential capability in our 20 air-independent propulsion submarines ($30B, $326B), our expanded surface fleet with a further 10 frigates ($10B, $316B), our F-35 Joint Strike Fighters and P-8 Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft.

We also need to boost our airborne capabilities with additional fighter aircraft ($25B, $291B) oriented towards maritime strike, land, and more air-to-air refuelling capacity ($1B, $290B) to support these fighter jets. We also need to enhance our land-based anti-air defences ($1B, $289B).

Closer to shore, we should expand our capability to utilise sea mines. Since World War II, mines have damaged and sunk more vessels than any other means; they are a highly effective asymmetric weapon that the ADF has only recently reintroduced into its inventory, and we should expand our capabilities and capacity in this area. ($1B, $288B).

At the same time, we need to beef up our anti-submarine warfare capabilities to protect our sea lanes, stop foreign submarines passing through choke points in our northern approaches and to protect our new strategic fleet ($20B, $268B), which Prime Minister Albanese promised but has not delivered on, critical for supporting continued economic activity and our defence effort in our northern coastal waters

Protecting defence, economic and population assets

In protecting Australia, we would need to have regard to keeping open our northern, naval and major ports, which would be vulnerable to enemy mines. Australia’s mine countermeasures have atrophied. This would have to be reversed ($5B, $263B).

Turning to ground forces, we need to be able to deal with lodgements on our territory or major raids. We need to be able, assisted by our geography, to oppose any march south, whilst also being able to supply our forces to the north. We need to double our heavy airlift capability with a further large transport aircraft ($4B, $259B).

Lessons from Ukraine are particularly relevant; the rise of drone systems and their effects on force architectures and land warfare, the effects of electronic warfare on the modern battlefield, the challenges of sustaining logistics in a contested environment (mindful of the huge distances involved in supporting Australian forces in the top end) and air defence.

In addition to existing Army programs, Australia must spend money to capitalise on the lessons learned. We need to be investing in drone and anti-drone capabilities ($2B, $257B), indigenous electronic warfare capabilities ($5B, $252B), 12 additional tactical transport aircraft ($2B, $250B), 48 additional utility helicopters ($2B, $248B), unmanned ground logistics vehicles ($2B, $246B) and shoulder fired anti-aircraft missiles ($2B, $244B).

Other priorities

Distance is not a barrier to effective cyber warfare. Australia must ensure our highly electronic and network-connected utilities are not disrupted by conflict. We need to increase investment in our cyber warfare capabilities ($5B, $239B).

We also need to address a huge deficit in our fuel security. ensuring we have a minimum 90 days in-country fuel supplies ($8B, $231B) and that we have a resilient general industry capability and self-sufficiency of critical commodities ($60B, $171B) that can keep the country running during conflict (or a pandemic).

Fuel security. What happens if the bowsers start to run dry?

We need to further learn the lessons of our Ukrainian friends and boost the capability and capacity to produce missiles and other munitions here. That includes the full gamut of weapons we use, from small arms to missiles to bombs to torpedoes, and many of the other consumables of war that can quickly run out. An investment in the order $10B is required ($5B, $166B).

Finally, the Government must stop embarking on highly costly and risky defence programs that don’t work out. It should be buying off-the-shelf capabilities, some built here where it makes sense, and enhanced by Australian industry. Industry would need to be configured to properly sustain all of our critical military capabilities onshore.

Yes, we can

With the US becoming more and more unreliable, it’s time for Australia to tilt to independence in defence. No-one can believe we are the US’s most important friend (the PM is still trying to get a meeting with Trump), or that they will stand by us in conflict. Those days have passed.

While China attacking Australia is a remote possibility, we must plan for the worst, an invasion of Australia. The good news is that the tyranny of distance is working in our favour. With determination and reform in Defence procurement, Australia can independently defend itself. We can make ourselves such a hard and difficult target that no one will try it on, or try to coerce us.

The numbers throughout this article show that we can cancel AUKUS and do what’s required, and walk away with over $150B left in consolidated revenue to do more for education, increasing productivity, economic advancement and social support.

Dumb Ways to Buy: Defence “shambles” unveiled – former submariner and senator Rex Patrick