Australia’s migration programme has failed to deliver what it promised. It brings in relatively few genuinely skilled workers, while favouring family migration. Professors Alan Gamlen and Peter McDonald suggest a better way.

Australia’s permanent migration system is incoherent, inefficient and in parts unlawful.

It delivers few new skilled workers while being clogged with family visas that, by law, should not be capped at all.

Meanwhile, temporary migrants—students, graduates and working holiday makers—carry the real weight of supplying skilled labour, yet are undervalued.

However, the migration programme is simultaneously presented to the public as both “capped” and “demand-driven”—a contradiction that undermines its credibility.

It needs two fundamental reforms: recognising the central role of temporary migrants in the skilled workforce, and separating skilled migration from family migration while redefining migration as primarily about skills, not family reunion. The overlooked reality is,

temporary migrants drive skilled employment.

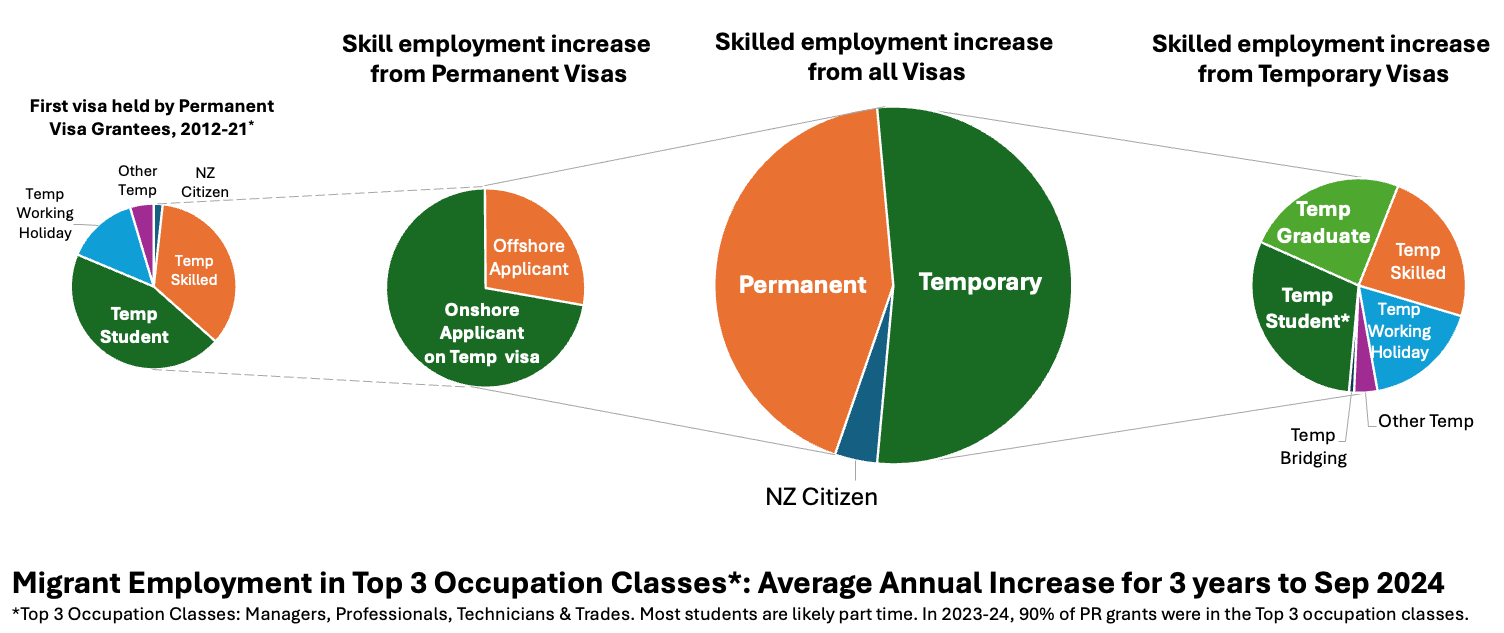

Public perception often assumes that skilled migration equals the Permanent Migration Programme. The opposite is the case.

Permanent vs temporary immigration

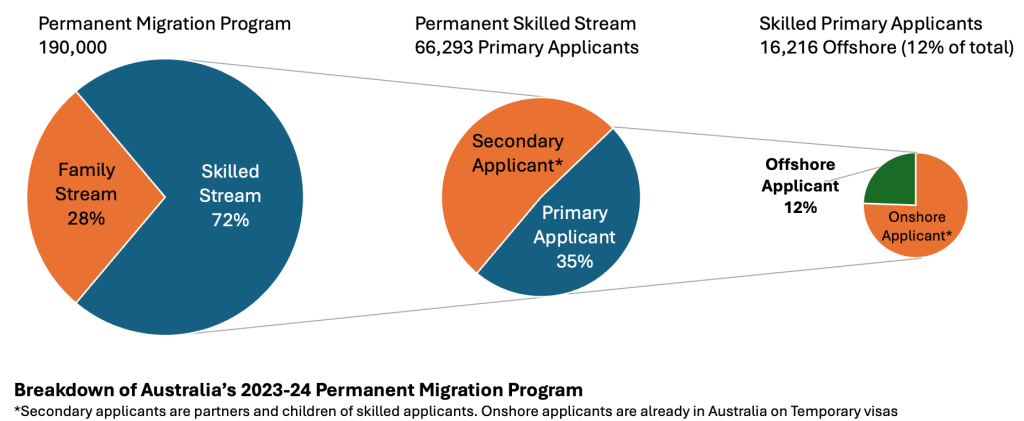

The permanent intake is capped at 185,000 people per year, of which around 30% is earmarked for family visas. Even within the Skilled Stream, the majority of visas do not go to skilled workers but to their families. Counting family and secondary applicants together, more than 60% of permanent visas are, in fact, family-related. Double the amount officially claimed.

Meanwhile, the share of genuinely new skilled arrivals from offshore is tiny—just 12% of the programme. The rest are already in Australia on temporary visas.

The Permanent Migration Program does little to bring new skills to Australia.

The real engine of skilled migration is temporary entry, not permanent. Over the past three years, 84% of the increase in migrant skilled employment has come from temporary migrants—especially international students, graduates and working holiday makers. These groups now underpin growth in high-skill occupations such as managers, professionals, and trades.

The value of student and graduate temporary migration has been misrepresented. Contrary to claims they mostly end up in low-skill jobs, census data show that over half of graduate visa holders work in high-skill fields. Their partners also contribute strongly. Working holiday makers, stereotyped as farmhands and bar staff, increasingly take up skilled positions.

Almost all recent increases in skilled migrant employment have been due to temporary migrants, especially students and working holiday makers. (Note. The 2024 estimates in this figure are obtained by applying 2021 Census employment characteristics for the various types of temporary visa to the numbers in the same visa types as of 30 September 2024.)

Yet these students and graduates face constant barriers. Graduate visa holders often find themselves in a “Catch-22” situation: they cannot get skilled work without permanent residence, but they cannot secure permanent residence without skilled work. This wastes talent and lowers productivity.

Construction industry

The stakes are especially high in construction, where labour shortages highlight the problem.

Australia faces a shortage of 130,000 tradespeople, with shortages of bricklayers, carpenters, electricians and other trades fuelling housing supply bottlenecks.

In 2023–24, the permanent programme delivered just 166 tradespeople—negligible against national needs. By contrast, more than 5,000 entered via the temporary skilled stream in 2024–25. Even this is insufficient to close the gap.

The only viable strategy is a dual one: expanding domestic apprenticeships while also increasing the skilled migrant flow. For the latter, employer-sponsored visas are the most effective pathway. They consistently deliver the strongest labour market outcomes. Yet they face growing demand and shrinking supply within the capped permanent programme.

Working holiday makers are increasingly filling gaps—especially under new agreements with the UK and Ireland. But as more take up skilled work, they too add pressure to the already overloaded employer-sponsored permanent visa system.

Failure to deliver skilled labour

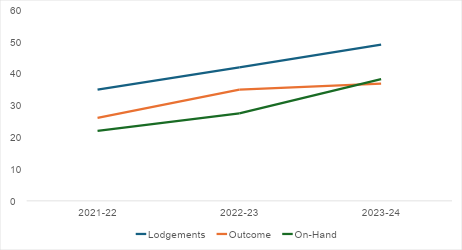

At the heart of the problem is the government’s failure to match employer-sponsored demand for permanent skilled visas, which is surging. In 2024–25, nearly 100,000 applications required processing, with only 44,000 places available. Employers who are used to a 98% approval rate now face inevitable delays and refusals.

Confidence in the system could collapse unless made predictable and efficient.

Employer-Sponsored Skilled Migration.

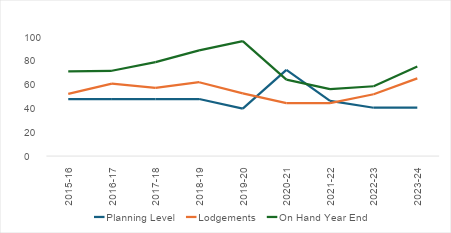

A key factor in the delays is that while family visas are officially described as demand-driven, partners and children of Australians are legally entitled to them under the Migration Act. However, in practice, they remain capped within the annual planning limit. That creates backlogs, hardship, and potentially unlawful administration.

Permanent Migration Program: Partner Visas.

For years, partner visa lodgements have far outstripped grants, creating queues of around 100,000 applications. Families endure waits of 15–25 months. Relationships strain. Skilled Australians sometimes leave the country rather than remain separated from loved ones.

The inconsistency is stark: partners of new skilled migrants (counted as secondary applicants) receive permanent residence immediately, with lower fees and fewer requirements, while Australian citizens’ partners wait years, pay more, and face stricter tests.

The law, however, is clear: partner and child visas cannot legally be capped under Section 87 of the Migration Act. Continuing to treat them as capped exposes the government to reputational and legal risks.

Separate skill from family migration

The solution is to redefine the Permanent Migration Programme to include only Skilled Stream primary applicants.

This reform would:

- Sharpen policy purpose: The permanent intake would be clearly about skills, not family reunion.

- Boost skilled migration: More places would be freed up for employer-sponsored and other skilled workers.

- Respect legal obligations: Family visas would be processed on a truly demand-driven basis, in line with the Migration Act.

- Restore confidence: Employers could trust that skilled migration pathways would remain predictable and efficient.

Humanitarian and parent visas would remain capped, while partner, child and secondary family applicants would move outside the programme cap.

The migration numbers game

Critics may worry that such reforms would blow out migration numbers. In reality, the impact on Net Overseas Migration (NOM) would be minimal.

Most permanent skilled migrants are already in Australia on temporary visas, and so are already counted in population statistics. Granting them permanency changes little in NOM.

The recent spike in migration numbers was largely due to fewer departures during the pandemic, not excess arrivals. Departures are now climbing again and will accelerate from 2027 as large cohorts of temporary visas expire.

Chasing short-term migration targets is as irrational as capping demand-driven visas. Migration is shaped by different arrival and departure streams, most of them uncontrollable. At best, migration can be guided like inflation—managed within a band.

Restoring clarity and confidence

Reform is overdue. By refocusing the permanent programme on Skilled Stream primary applicants and treating family visas as truly demand-driven, Australia can restore coherence to its migration framework. This would strengthen pathways from temporary to permanent residence,

ensure skilled shortages are addressed, and rebuild employer confidence.

Such reforms would not inflate migration numbers but would make the system more transparent, lawful and effective in meeting Australia’s long-term economic and social needs.

This article originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.